The big-box game

The largest container lines are bulking up to try to withstand a fresh downturn

SINCE the financial crisis, the tide of recovery has not lifted all boats equally. But in few industries is that more true than in shipping. Demand for oil tankers has boomed: a combination of weak spot prices and higher futures prices, driven by the assumption that supply and demand for crude will eventually rebalance, has encouraged traders to hire tankers to store oil at sea and cash in on the price gap. Meanwhile, bulk carriers, which carry such things as iron ore and coal, have been hit by massive overcapacity, as Chinese demand for such commodities has collapsed (see article).

Until the start of this year, the container-shipping business—which carries around 60% by value of all seaborne trade in goods—looked more like that for oil tankers. Rising global trade volumes, and firm steel prices that made it worthwhile for owners to scrap old ships, had kept capacity in check, and container-freight rates seemed to be steadying. As recently as August last year, demand for container shipping was so high that BIMCO, an industry association, was warning of a capacity shortage. And at the start of this year Drewry, a shipping consultant, forecast a bumper year: owners of boxships would rake in profits of up to $8 billion in 2015, they thought, helped by low fuel costs.

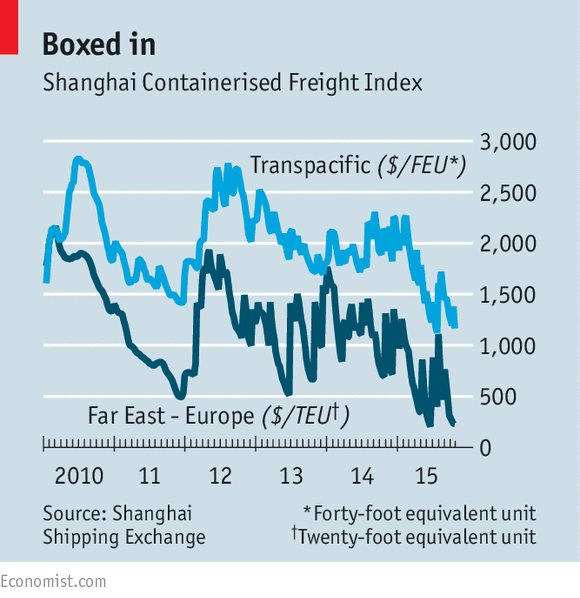

But since then the industry has been rattled by renewed weakness in freight rates, prompted by a fall in the volume of seaborne trade. The cost of sending a container from Shanghai to Europe, for instance, has almost halved since March, according to the Chinese city’s shipping exchange (see chart). And the absence of the usual pre-Christmas pick-up is worrying both analysts and investors, according to Rahul Kapoor of Drewry. On October 23rd Maersk, the world’s largest container line, told investors to brace themselves for a fall in profits when it announces its third-quarter figures on November 6th.

Advertisement

|

Some of the shipping lines’ problems are due to factors beyond their control. At a time when weak trade volumes should be prompting them to scrap more old vessels, the steel price has slumped. So, 60% fewer boxships have been scrapped so far this year compared with the same period last year. However, some shipping groups have made a rod for their backs by taking on too much debt. This also makes it hard for them to scrap unprofitable vessels, since their balance-sheets would struggle to cope with the resulting writedowns.

Worse still, critics say, is that shipowners have embarked upon a building boom. Orders for new container ships were 60% higher in the first five months of this year, than in the same period in 2014, according to Alphaliner, a data provider. In June Maersk ordered 11 ships that can each carry up to 20,000 standard-sized containers, in a deal worth $1.8 billion. Next week Hapag-Lloyd, another operator, plans to raise $300m by floating on Frankfurt’s stock exchange, to help pay for six giant new ships, ensuring that it stays in the game.

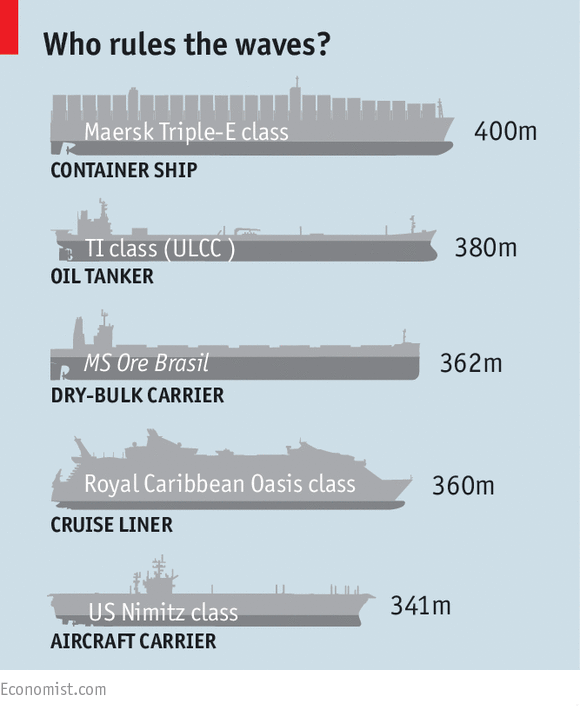

Hapag-Lloyd has had to delay its IPO a week because demand for the shares has been so weak. And investors have good reasons to be hesitant. All the extra capacity should depress rates further, adding to the industry’s problems. But for those lines that can afford it, ordering big, new ships may be a sensible reaction to falling freight rates. There are still sizeable economies to be gained from increasing the size of vessels. As Hapag-Lloyd’s boss, Rolf Habben-Jansen, recently pointed out, a ship capable of carrying 19,200 containers needs half as much fuel to shift each box by one mile as a vessel with a capacity of 4,900.

As a result, the capacity of the largest container ships afloat has risen from around 14,000 before the financial crisis to just under 20,000 today—and boxships are taking the place of oil supertankers as the giants of the seas (see diagram).

Among the winners from this flight to scale will be the world’s largest three lines—Maersk, Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) and CMA CGM. They have the industry’s lowest costs, because they have the biggest ships and the cheapest finance costs. They also have the advantage of being based in Europe: demand to transport goods across the Atlantic has remained strong. Analysts expect the big three to stay profitable over the next few tough quarters, even as their revenues fall.

Maersk and MSC have also formed an alliance, 2M, to save more money by sharing space on their ships on transatlantic and transpacific routes. As the strongest lines get stronger, through fleet renewal and alliance-building, smaller lines that cannot cut their costs quickly enough or obtain cheaper finance to build bigger ships will suffer. China’s two biggest lines, China Shipping Group and Cosco, were losing money before the current downturn started. They have recently swung back into profit, but only thanks to generous state aid to help them scrap old vessels. The government regards it as vital to have a national merchant fleet, so it will not let the two go to the wall. But it plans to merge them to save money, and to stamp out corruption at Cosco which, according to internal documents leaked this week, is another reason for its poor performance.

The hardest hit, however, will be the smallest container lines that do not enjoy state backing. Several smaller Japanese and South Korean operators, in particular, are sailing close to bankruptcy, analysts say. The pressure to cut costs is also hitting container lines’ suppliers; several shipping-services firms in Denmark and container-logistics firms in Britain have gone bust in the past year.

The move towards ever bigger vessels poses a risk to ports which lack the capacity to handle them. International trade is shifting towards big, centralised hubs. And smaller ports, somewhat like smaller airports when the hub-and-spoke model for long-haul flights became dominant, are losing many of their direct connections. This has already happened at Portland on America’s west coast, which is no longer served by any regular container routes.

To avoid this fate, port authorities in some countries are now investing heavily in upgrading their infrastructure, to handle larger vessels. Recent development projects in Liverpool and London have already brought traffic back to those British ports. In a similar vein, Indonesia announced details of a $3.6 billion project to upgrade its container ports earlier this month, to ensure it does not lose routes to Singapore, the nearest big hub.

As falling volumes and weak shipping rates force the industry to consolidate, with fewer, bigger lines sailing ever-larger ships to fewer, bigger ports, the resulting gains in efficiency should mean cheaper transport costs, bringing benefits for consumers in many places. That is, unless the consolidation goes too far, and the surviving lines are able to jack up their rates. The 2M alliance now controls more than 28% of global container-shipping capacity, and almost a third on the Europe-to-Asia route.

Regulators are already worried about the impact on competition: in June last year, the Chinese authorities vetoed plans for a larger alliance, called P3, that would have involved all three of the world’s biggest lines. Cheaper container rates are a boon for firms engaged in international trade, and their customers. But there is a risk that the benefits will not last.

No comments:

Post a Comment