Are global wages about to turn?

- 3 hours ago

- From the section Business

- 72 comments

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images

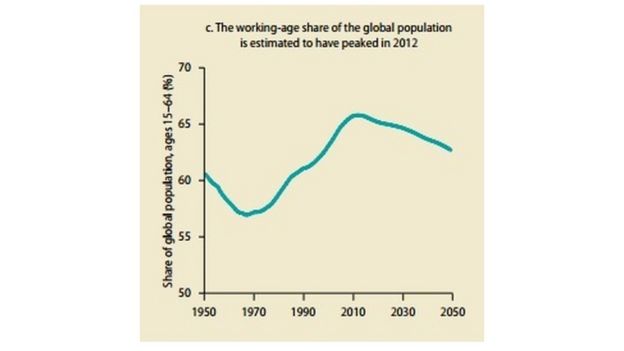

"The working-age share of the population peaked in 2012 and is now on the decline." This is probably the single most important sentence published this week from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund - but it comes from an unlikely source.

The IMF and the Bank are holding their semi-annual meetings in Peru. As usual this is being accompanied by a plethora of reports and forecasts from the two global institutions' staff teams covering the whole gamut of global economic policy. The headlines have been grabbed by the new forecasts in the World Economic Outlook (WEO) showing a weakening global recovery and particular problems in the emerging economies.

But it's the The Global Monitoring Report, the publication which tracks progress towards the Millennium Development Goals - which rarely gets much attention - that has that crucial line (so crucial it's worth repeating): "The working-age share of the population peaked in 2012 and is now on the decline."

What makes that sentence so important is that it applies to the global population.

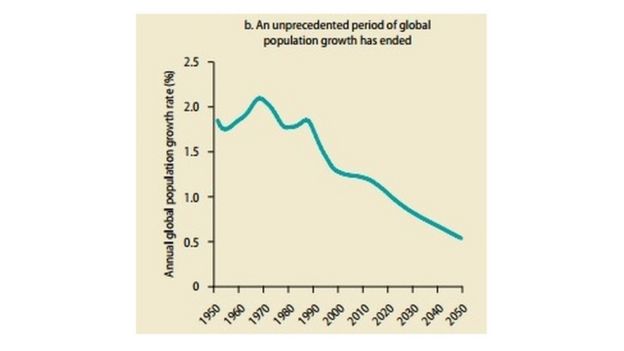

The Monitoring Report makes clear that the planet is on the verge of a huge demographic shift, a shift neatly summarised in two charts.

A global turning point

First, after decades of fast growth, world population expansion is slowing. Image copyright Global Monitoring Report

Image copyright Global Monitoring Report But that's not all. The share of the global population of working age (defined as 15 to 64) is forecast to fall.

Image copyright Global Monitoring Report

Image copyright Global Monitoring Report In the long run, demographics matter hugely to the economy and that long run may arrive quicker than we think it will.

The 1970s and 1980s saw the advanced economies enter what demographers have called a "sweet spot" as the post-war baby boomers entered the workforce and declining fertility rate reduced the number of dependent children. The working-age share of the population rose strongly.

That trend was then turbo-charged by the entry of China and the former Soviet bloc into the world economy. The global workforce available to firms roughly doubled in two decades.

In other words, for roughly four decades (and especially so in the last two) "labour" has been in broad supply. But if the global glut of workers is set to end - driven by both slowing population growth and a falling working-age share - then that could have major impact on global economics.

Wages up and inequality down?

The implications of this demographic change have been examined by both former Bank of England Chief Economist Charles Goodhart and by fund manger Toby Nangle (and I've blogged on both of their analysis).The Goodhart-Nangle view is that a combination of demographic change and China's entry into the global system can explain some of the bigger trends observed in advanced economies over the past few decades and that the ending of the "sweet spot" could see these trends reverse.

In particular they both have interesting things to say on both wage growth and interest rates.

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images That fell to 1.5% in the 1990s, and 1.2% between 2000 and 2010. A smaller workforce though should raise demand for workers, restore some bargaining power and could see that trend of declining real wage growth reverse.

And, as Charles Goodhart has argued, a trend towards rising real wages could have important implications for inequality. As the relative returns on labour versus capital rise one would expect inequality to fall. In other words, Professor Piketty may be wrong to fret about ever rising inequality - demographic change should bring it down.

When I last blogged on demographics, wages and inequality I received a large amount of feedback via Twitter of varying degrees of politeness. To many the idea that a global demographic change - rather than changing tax rates, the growth of finance, the decline of trade unions or some amorphous concept that goes by the name "neoliberalism" - has driven inequality is contentious.

Policy still matters

Image copyright Getty Images

Image copyright Getty Images In January this year, the final report of the Commission on Inclusive Prosperity (ran by the Center for American Progress and chaired by Ed Balls and Larry Summers) found that low and middle-income workers in countries has diverse as Australia, Canada, France, Japan, Sweden, the UK and the US had all seen a multi-decade wage growth slowdown.

These are countries with vastly different tax laws, vastly different financial industries (in terms of their size and structures) and radically different trade unions (in terms of laws, coverage and raw size).

All have seen the same broad trend and that perhaps is a clue that something bigger has been going on in the background. Workers have done better (in terms of wage growth) in some countries and the rise of inequality has not been entirely uniform.

National policymakers aren't powerless in the face of global trends - different labour laws, different tax systems and different economic policies will lead shape and shift what happens to wage growth and inequality. But they only shape and shift, they don't fully determine the outcome.

For four decades demographic trends have acted as a headwind to wage growth. That now may be becoming tailwind. But the exact outcomes will vary from country to country.

No comments:

Post a Comment